登录

创建你的网站

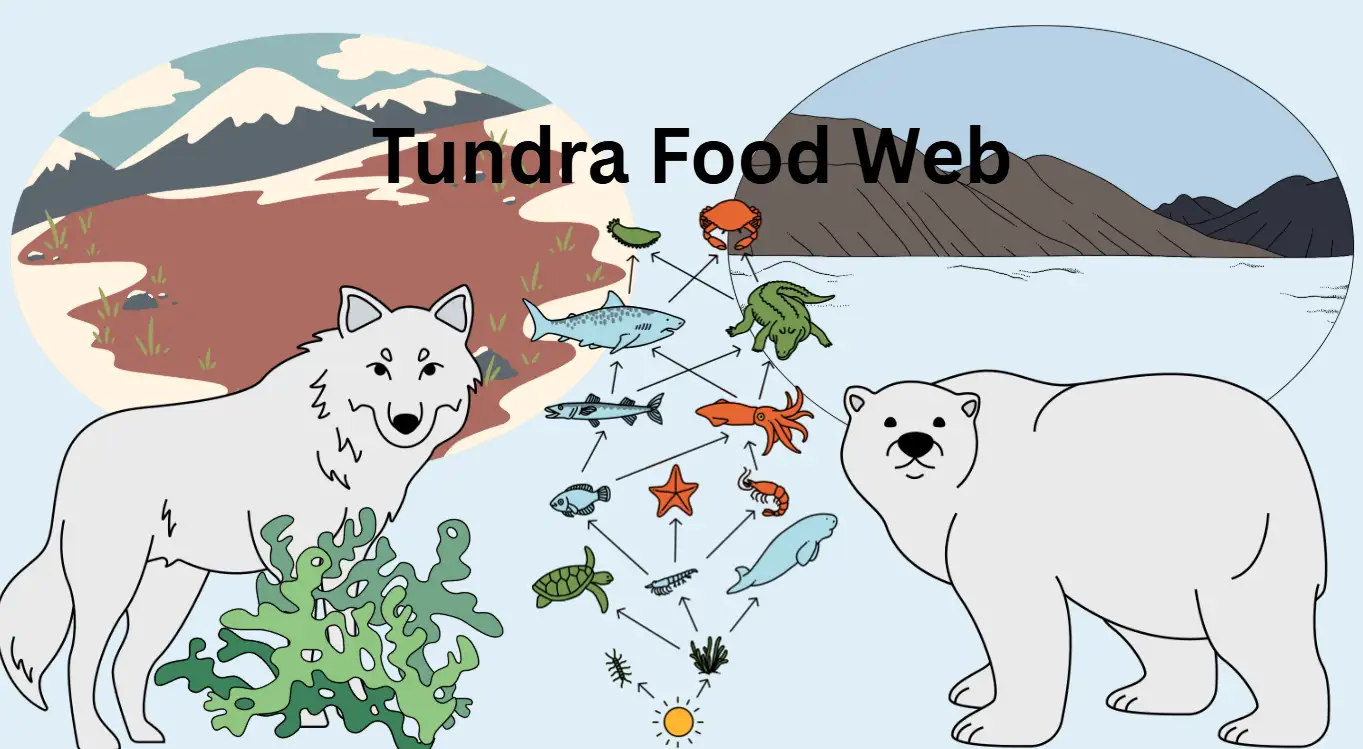

20 Organism Food Webs in the Tundra: Visual Examples for Students

Need Tundra food web examples with 20 organisms? This student-friendly guide features visual diagrams that explain predator-prey roles in Arctic ecosystems.

Ever wondered how life survives in several of the harshest environments on Earth? I've spent years studying the Arctic biome, and now I am eager to talk about what is so fascinating about the tundra's food web. In this cold place, it is difficult for us to understand how organisms interact and survive with each other. Many learners find tundra food chains difficult to understand because they are so different from the biological environments they are familiar with.

The tundra ecological environment is considered the most extreme biological community on Earth. The temperature there can decline to -40 degrees Fahrenheit, and plants can only grow normally for 2 to 3 months each year. Regardless of the harsh conditions, the Tundra food web examples with 20 organisms here is thriving. They must understand what's going on in these Arctic tundra food chains, as global warming is harming these vulnerable communities.

In this comprehensive guide, I'll walk you through using every aspect of the Tundra food web examples with 20 organisms. These real species all have their areas of expertise, and they survive by helping each other. After reading this, you'll understand how these Arctic tundra food chains affect the fate of the Earth.

What is the Tundra Food Web?

Tundra food webs are a complex web of connections in which organisms prey on each other in the Arctic and alpine tundra regions. Food chains are usually simple, a straightforward “who eats whom” pattern. Nevertheless, the tundra trophic web is much more complex, such as an enormous grid with various organisms occupying different trophic levels.

The trophic web in the tundra is undergoing stress and developing in an environment that is completely different from anywhere else. The short growing season, frozen ground, and inclement weather create unique foraging relationships. Primary producers like mosses, lichens, and grasses, which are particularly frost-resistant, offer a base for herbivores that can digest and assimilate the less nutritious plants.

Key Characteristics of Tundra Food Webs

- Simplified structure: Fewer species than temperate ecosystems

- Seasonal variations: Dramatic shift between summer and winter feeding patterns

- Energy efficiency: Organisms maximise energy conservation due to harsh conditions

- Slow decomposition: Cold temperatures slow nutrient cycling

- Specialised adaptations: Unique feeding strategies for extreme environments

Tundra food chains generally have fewer trophic levels than tropical biomes. The main herbivores living there are caribou, Arctic hares, and lemmings. Secondary carnivores, like Arctic foxes, snowy owls, and wolverines, hunt herbivores to fill their stomachs. Top predators such as polar bears and wolves are at the top of the food chain.

2025 Tundra Food Web Examples with 20 Organisms

To superior illustrate how complex Arctic ecosystems are, let's look at Tundra food web examples with 20 organisms. All organisms play a crucial role in keeping the delicate ecological balance in these harsh environments.

Primary Producers (4 organisms)

- Arctic Moss (Racomitrium lanuginosum) The mosses, one of the Tundra food web examples with 20 organisms, in the Arctic grow densely, such as a mat, and they form a critical basis for the food chain of many organisms on the tundra. This tough moss can withstand extreme temperature changes and grow slowly in soil with very few nutrients. It retains water, so it can survive long periods without rain, making it particularly critical to animals that eat grass in the winter when other food is hard to find.

- Caribou Moss (Cladonia rangiferina). Regardless of its name, caribou moss is a type of lichen that is a major food source for many Arctic herbivores. This life form grows very slowly, taking decades to reach full size, and provides critical, energy-dense nutrition to enormous mammals. It uses the short Arctic summer to photosynthesise, a trait that makes it a cornerstone species in Tundra food web examples with 20 organisms.

- Arctic Willow (Salix arctica) Arctic willow is one of the rare woody plants that can grow well in the tundra. This low shrub is a critical forage for herbivores year-round. Its well-developed root system is particularly good at holding water and soil, preventing soil erosion. Moreover, in early spring, when other plants are still hibernating in the frozen soil, it begins to grow and offer critical nutrients.

- Cottongrass (Eriophorum vaginatum) Cotton grass grows particularly well in moist tundra areas, and it provides critical nesting material for many bird species. Its seeds are particularly rich in oil, allowing migrating birds to store more energy. This plant is easily recognisable by its distinctive clusters of white, fuzzy seeds and is a critical link in the nutrient chain of the Arctic tundra.

Primary Consumers (6 organisms)

- Caribou (Rangifer tarandus): Caribou are the centrepiece of Tundra food web examples with 20 organisms. Their enormous herds assist many predators and scavengers. These big herbivores are amazing. Their digestive systems are specially customised to digest low-quality plants, like lichens that other mammals cannot chew. They migrate back and forth with the seasons, bringing various nutrients to the vast permafrost zone and connecting different ecosystems.

- Arctic Hare (Lepus arcticus): Arctic hares are well adapted to extreme cold weather. Their thick white fur not only keeps them warm but also helps hide them from enemy eyes. These herbivores can reach speeds of 40 mph when escaping predators, making them challenging prey. Their ability to find vegetation beneath snow makes them year-round residents of the tundra.

- Lemming (Lemmus lemmus): Lemmings are one of the most critical small mammals in the food chain of the Arctic tundra. They rely on periodic "population surges" to feed an enormous number of predators. They reproduce very quickly and can enlarge rapidly once environmental conditions are right, providing sufficient food for foxes, owls, and other carnivores. Their digging activity helps to aerate frozen soil.

- Musk Ox (Ovibos moschatus): Musk oxen are giant herbivores with dense, shaggy fur that can withstand temperatures as low as -40 degrees Fahrenheit. When these animals are in danger, they will form a circle to protect themselves and use their curved horns to butt against those who want to eat them. Their habit of searching for food everywhere actually protects the growth of various plants in the fragile tundra ecosystem.

- Ptarmigan (Lagopus muta): This bird, called Ptarmigan, lives exclusively on the ground and switches the colour of its feathers according to the season to avoid predators. They have feathers on their feet that act as snowshoes, allowing them to walk on the snow without sinking. These birds mainly eat shoots, leaves, and berries and are also critical prey items for various predators.

- Arctic Ground Squirrel (Spermophilus parryii): Arctic ground squirrels are the only mammals that can hibernate in the Arctic. In winter, their body temperature can drop below zero degrees, which is very cold. In the summer, they begin to store fat and dig many interconnected caves so that other small animals can hide in them. Their storage behaviour helps spread seeds throughout the tundra.

Secondary Consumers (6 organisms)

- Arctic Fox (Vulpes lagopus): The Arctic fox is a highly adaptable predator whose coat colour switches with the seasons, from brown in the summer to white in the winter. They have incredibly good hearing, which allows them to spot prey hiding under the snow. These foxes always follow polar bears, hoping to eat the seal meat left by polar bears, which just reflects their foraging habits of finding loopholes in the tundra food chain and eating whatever they can.

- Snowy Owl (Bubo scandiacus): The Snowy Owl is a very powerful hunter. Its asymmetrical ear holes allow it to identify prey in the snow with its extraordinary hearing. Their thick feathers provide insulation while hunting, so they are not afraid of the cold when running. These birds can detect lemming movements from over a mile away, making them great for navigating the vast tundra.

- Wolverine (Gulo gulo): Wolverines are the largest land animals in the Mustelidae family, and their preeminent vitality and endurance impress everyone. They can travel up to 40 miles a day in search of food and have robust jaws capable of crushing bones. Their scavenging behaviour helps clean up carcasses.

- Ermine (Mustela erminea): Ermines are small but fierce predators and are particularly good at climbing trees, so they can catch prey either on the ground or in trees. Their snow-white winter fur is completely hidden in the snow and cannot be seen at all. These hunters can take down prey that is much greater than themselves, like rabbits and ground squirrels.

- Gyr Falcon (Falco rusticolus) Gyr falcons are the largest falcons in the world and can swoop at astonishing speeds, reaching up to 130 miles per hour when chasing prey. Their robust claws and pointed beaks make them great hunters of ptarmigan and other birds. These birds of prey like to build their nests on the edge of cliffs. They have extremely powerful eyes and can see their prey miles away.

- Arctic Char (Salvelinus alpinus): Arctic char, a cold-water fish, represents crucial components of the aquatic Tundra food web examples with 20 organisms and is a critical part of the entire ecosystem. Their antifreeze proteins prevent ice crystals from growing in their blood, allowing them to survive in nearly freezing water. These fish are a critical source of protein for the bears, seals, and birds that hunt in the tundra's lakes and rivers.

Tertiary Consumers (2 organisms)

- Polar Bear (Ursus maritimus): Polar bears are top hunters that have adapted to the Arctic marine environment. The hollow fur on their bodies is extraordinary for maintaining warmth and floating. Their noses are so good that they can smell a seal from 20 miles away. These extensive carnivores initially prey on seals, but will feast on whale carcasses and hunt other mammals when given the chance.

- Grey Wolf (Canis lupus): Grey wolves form organised packs, which allow them to more effectively hunt gigantic prey like caribou and musk oxen. Their cooperative hunting strategies allow them to take down animals many times their size. These predators are responsible for controlling the size of herbivores there, and the seriousness of their activities directly affects the foraging distribution of animals on the tundra.

Decomposers (2 organisms)

- Arctic Bacteria (Psychrophilic bacteria): Arctic bacteria are particular microorganisms that can survive in extremely low temperatures. The cold shock proteins in their bodies help them work normally in icy environments. These bacteria slowly break down organic matter, returning nutrients to the ecosystem. They are noticeably less active in the winter, but are active year-round.

- Tundra Fungi (Cladosporium herbarum): Tundra fungi are very critical. They can not only decompose dead plants, but also establish a good relationship with the roots of plants, forming a symbiotic relationship of mutual help. Their frost-resistant enzymes are particularly powerful and can continue to decompose various substances even when the temperature declines below zero. These organisms help recycle nutrients in soil layers that never fully thaw.

Interconnected Relationships

These Tundra food web examples with 20 organisms illustrate the complex interdependencies in Arctic ecosystems. Each species has evolved its unique skills to survive in a particular harsh environment. This has formed a very delicate balance, but climate change is now threatening it. The interactions between these organisms form multiple pathways for energy to flow. When the number of lemmings suddenly declines a lot, Arctic foxes may switch their diet and catch birds to eat, or find several animal carcasses to chew on. Similarly, the caribou's annual migration route will determine where hunters choose to settle in this vast tundra.

What are Decomposers in the Arctic Tundra?

Decomposers responsible for breaking things down in the Tundra food web examples with 20 organisms, have unique problems that set them apart from their counterparts doing the same job in warmer climes. These life forms have to survive in a climate that would kill most organisms, but they are extremely critical for nutrient cycling in the tundra trophic chain.

Cold-Adapted Microorganisms

The primary decomposers in Arctic tundra food chains consist of specialised bacteria and fungi that have gradually adapted to the extremely cold environment. These microbes produce antifreeze proteins and adapt their cell membranes so that they remain flexible in climates that freeze most biological structures.

- Psychrophilic bacteria represent the most abundant decomposers in tundra ecosystems. These creatures can survive in temperatures as low as -10 degrees Celsius and are quite active all year round, although they slow slower in the winter. They slowly but steadily break things down so that organic matter doesn't build up too much.

- Cold-tolerant fungi form the second major group of tundra decomposers. These life forms often work with plant roots to build mycorrhizal networks that help plants absorb nutrients from poor soils. Their enzyme systems remain active at low temperatures, allowing them to break down complex organic compounds.

Decomposition Challenges in Tundra Environments

- Slow decomposition rates: Cold temperatures decrease enzyme activity by 90% compared to temperate environments

- Permafrost barriers: Frozen soil layers prevent deep decomposition

- Seasonal limitations: Most decomposition occurs during brief summer months

- Nutrient cycling delays: Organic matter can remain partially decomposed for decades

- Specialised adaptations required: Only highly adapted organisms can survive these conditions

Tundra food web examples with 20 organisms decompose at different rates, creating unique ecosystem dynamics. As organic matter is left for a long time, it will accumulate and become a thick, semi-rotten layer called the active layer. Its continued accumulation eventually led to a switch in the soil composition and plant growth patterns in the ecosystem.

Impact on Tundra Food Webs

Decomposer activity directly influences the entire Tundra food web examples with 20 organisms. The gradual restriction of nutrient cycling affects plant productivity, which has an influence on herbivore populations, which in turn affects predator populations. The activity of decomposers occurs all at once in the summer, creating a seasonal burst of nutrients. These decomposers also play crucial roles in carbon cycling. In the food chain of the Arctic tundra, things decompose slowly, which means that there is still a lot of carbon locked in the permafrost. They found that climate change could cause things to decompose faster, making it easier for buried carbon to escape, which could ultimately disrupt global climate patterns.

What are Primary Consumers in the Arctic Tundra?

Primary consumers in Arctic tundra food chains have evolved unique survival skills that allow them to survive in one of the harshest environments on Earth. These herbivores must obtain adequate nutrition from plants of low nutritional value in an environment of extreme cold and food scarcity.

Large Herbivores

- Caribou: Caribou are one of the most critical primary consumers in the Tundra food web examples with 20 organisms. These creatures have evolved a powerful digestive system specifically designed to deal with lichens, which are indigestible to most other mammals and have little nutritional value to them. Their four stomachs help them digest even the less-than-good grass to the maximum extent possible.

- Musk oxen: It has insulation about as good as modern synthetic materials thanks to its dense undercoat, so they are exceptionally hardy in cold weather. These gigantic herbivores can dig through the snow to find their food, and they have powerful jaw muscles to chew even tougher plants. Their grazing patterns help maintain plant diversity in fragile tundra ecosystems.

Small Herbivores

- Lemmings: They may be only the size of a palm, but they play a key role in the Tundra food web examples with 20 organisms. When environmental conditions are right for population expansion, these rodents reproduce rapidly, leading to boom-and-bust cycles for entire ecosystems. They dig holes, which allows the frozen soil to breathe and distribute nutrients.

- Arctic hares: They have evolved the ability to run very fast and hide well in order to avoid natural enemies in the open tundra areas. Their gigantic hind feet act such as snow boots, allowing them to travel efficiently on snow-covered terrain. These herbivores can use their sensitive noses to smell vegetation beneath the snow.

- Ptarmigan: It stays in the tundra area all year round and is considered the main bird there. Their feet are covered with thick feathers, which not only keep them warm but also help them to grip firmly on the slippery ice. Their feathers also switch colour with the seasons, helping them to avoid natural enemies. These birds eat buds, leaves, and berries during warm weather.

Feeding Adaptations

- Efficient digestion: Specialised gut bacteria help process low-quality vegetation

- Energy conservation: Reduced activity during harsh weather conditions

- Food storage: Caching behaviours for surviving winter months

- Seasonal migrations: Moving to areas with superior food availability

- Social feeding: Group foraging to locate scattered food sources

Seasonal Feeding Patterns

In Tundra food web examples with 20 organisms, primary consumers have to constantly adjust the way they find food in response to extremely variable seasonal conditions. During the brief periods of warm weather, these creatures focus on gaining weight quickly to survive the long winters when food is scarce. In warmer seasons, they eat particularly high-quality vegetation, like newly grown sprouts, flowers, and various berries. During this brief time of abundance, organisms improve their nutrient intake. Many species also store food for the winter, creating deep-hidden reserves in their territories. During cold weather, finding food becomes a problem because most plants are covered with snow or frozen. Primary consumers have to rely on previously stored food, or they have to dig by using the snow to find plants, or they have to shift to a place where there is more food. Sometimes they choose to enter a shallow hibernation so that they can consume less energy.

Population Dynamics

The number of primary consumers in the Arctic Tundra food web examples with 20 organisms fluctuates greatly depending on how much food they can eat and the pressure of being eaten by other animals. Lemming populations are notorious for their boom-and-bust cycles, typically peaking every three to four years and then rapidly declining. These population cycles affect the entire tundra food web structure. When primary consumer populations peak, predator populations typically optimise the following year. When there are suddenly fewer herbivorous animals, the carnivorous animals have to quickly find other food; otherwise, they will suffer and their numbers will drop. Understanding these population dynamics can help scientists predict what effects climate change may have on the Arctic tundra food web. Increasing temperatures might cause plants to grow differently, and so the delicate balance between primary consumers and the food they eat might be disrupted.

Ecological Importance

Primary consumers act as key links between larger trophic levels in plant communities and tundra food webs. Their habit of eating from all directions helps to keep a variety of plants alive and prevents one type from taking over too much territory.

Their movement patterns also distribute nutrients across vast tundra areas. These herbivores engineer their environment through their feeding and burrowing activities. Caribou trails create pathways for other animals, and lemming burrows offer a good hiding place for many small animals. Their presence shapes the appearance of the tundra terrain.

Building Your Educational Platform with Wegic AI

Develop a user-friendly platform that allows learners to easily explore detailed academic material on the Tundra food web examples with 20 organisms. Using an AI-powered website builder - Wegic, you can turn teaching materials into an aesthetic website! Wegic revolutionises website development by using conversational communication, making it ideal for teachers who want to communicate complex scientific concepts without being bogged down by technical difficulties. Tell us about your plans to present the details of Arctic habitats, and about the amazing no-code website that Wegic will use its talent to build, which will use animations to show students how trophic networks in the tundra work.

Whether designing an interactive learning session about Arctic Tundra food web examples with 20 organisms or a graphic that shows the connections between complex ecosystems, Wegic provides AI tools to use for work to make academic content more accessible and fun. Start building your teaching platform now to make teaching about tundra ecosystems a fun adventure that your students won’t forget.

撰写者

Kimmy

发布日期

Jul 24, 2025

分享文章

阅读更多

我们的最新博客

Wegic 助力,一分钟创建网页!

借助Wegic,利用先进的AI将你的需求转化为惊艳且功能齐全的网站

使用Wegic免费试用,一键构建你的网站!